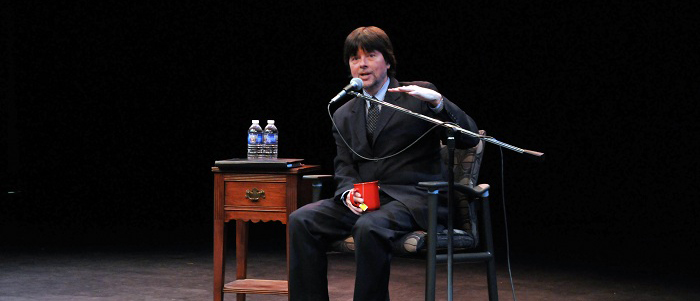

“What would you change in history if you could?” asked a student of documentary filmmaker Ken Burns. “I would stop the assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” he answered. “I am curious as to what Lincoln’s emphasis on our better angels after the Civil War… what might have happened.”

Burn’s answer was central to the hour-long master class he led with Media Arts, Jazz and Academic Studio students at NOCCA in October. “Who are we is the question that has animated my life’s work.”

His life’s work has earned him seven Emmy’s and two Oscar nominations for renowned documentaries that include The Civil War (1990), Baseball (1994), Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery (1997), Jazz (2001), Mark Twain (2001), The National Parks: America’s Best Idea (2009), Prohibition (2011); and upcoming films on Jackie Robinson, The Roosevelts and Vietnam.

In answering another student, Burns was able to show NOCCA’s young artists how stories and biographies are interconnected. “What drew you to jazz?” a jazz student wanted to know. “After The Civil War and Baseball, I realized I was working on a trilogy,” Burns explained.

“The Civil War was hugely important. Everything before let up to it, everything after is the result. The game of baseball was an entre into social life and race. And the period music was all jazz. Jazz was created out of circumstances not conducive to art. It was born of a community with a memory of being unfree in a free land. It is the timeless affirmation even in tough times.”

“Tell a good story,” he said simply, “and everything comes in its wake.” To tell a good story, the director offered insights into his pioneering techniques: using a chorus of voices and narrators, performing period music on period instruments, forsaking storyboarding, shooting on film, not being seduced by all of the good stuff on the editing room floor, and keeping an open script process so he can constantly add and subtract information and happy coincidences.

And, of course he spoke of his pan and zoom process. “You start at the bottom of a picture that shows two gun holsters… and slowly pan up to a child’s face. It all goes back to telling a story.”

Burns’ own story as a filmmaker began when he was 12. How a movie could make his father cry after his mother’s death helped him understand the power of art. He went on to study filmmaking at Hampshire College under photographer Jerome Liebling. “If I hadn’t met him,” Burns answered a student’s question about his mentors, “you would not be meeting me.”

“Filmmaking is not easy and nothing will be handed to you. It is 12 – 14 hours work a day, six to seven days a week. We will work years on a film: 10 years on The National Parks, five and one half on The Civil War, six on Jazz. You have to know who you are. The key to success is being honest and working hard.”

“Great men do great things,” he offered to NOCCA’s young artists, “but they are not the only stories. I’ve found out there’s no such thing as ordinary people.”